Single-Subject Experimental Design for Evidence-Based Practice PMC

Table Of Content

Few studies to date have examined ASD services and their relationship to patient outcomes simultaneously. As a retrospective study using clinical data, there were some study limitations inherent to the design and dataset. The study sample was clinical in nature, and thus children in the sample may have had more severe ASD than the general ASD population. Most children in the sample had commercial insurance subject to a state autism mandate, limiting conclusions that can be drawn about the Medi-Cal population. We were unable to capture patient outcomes for those who discontinued ABA or to measure ABA fidelity, as well as variables not collected as part of routine healthcare including school outcomes and socioeconomic characteristics of families (e.g., family income, parent employment).

Experimental Design

Similarly, studies aiming to improve proficiency in a skill through practice may not experience returns to baseline levels when the intervention is withdrawn. In other cases, the behavior of the parents, teachers, or staff implementing the intervention may not revert to baseline levels with adequate fidelity. In other cases still, the behavior may come to be maintained by other contingencies not under the control of the experimenter. The authors discuss the requirements of each design, followed by advantages and disadvantages. The logic and methods for evaluating effects in SSED are reviewed as well as contemporary issues regarding data analysis with SSED data sets.

Sample Description

At first baseline data is taken on all participants, and then participants are given treatment over time. The interventionists identified the six one-step directions that each participant responded to with the lowest accuracy, and within each category (i.e., fine-motor and gross-motor movements), randomly assigned them to experimental conditions (MTL, LTM, and control, see Table Table2).2). There was one exception to this rule; in error, two gross-motor responses were assigned to the MTL condition and two fine-motor responses were assigned to the LTM condition for James. The fact that the response effort for the MTL condition was higher did not affect its effectiveness and efficiency, as further described in the “Results” section. Although many behaviors would be expected to return to pre-intervention levels when the conditions change, others would not. For example, if one's objective were to teach or establish a new behavior that an individual could not previously perform, returning to baseline conditions would not likely cause the individual to “unlearn” the behavior.

Predictors of Patient Adaptive Behavior Outcomes

The goal is to increase behaviors that are helpful and decrease behaviors that are harmful or affect learning. Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is a therapy based on the science of learning and behavior. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. The first author received financial support from the Graduate Center, CUNY, to present the research data at the ABAI 41st Annual Convention in San Antonio. To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account.Find out more about saving content to Google Drive.

Products and services

The authors concluded that the MTL procedure with a time delay should be the default procedure used for teaching skills to children with ASD whose instructional history is unknown. The results of the between-groups comparisons in this scoping review indicated that 23 comparison records compared intensive ABA (20–40 hr of intervention per week) to control or other interventions. Existing literature indicates that 30–40 intervention hours per week for children under the age of 6 results in greater improvements in cognition, language development, social skills, and more (Kovshoff et al., 2011; Reed et al., 2007b). That said, more recent large-scale analyses on children who received 12 months of ABA services indicated that increased intensity does not necessarily predict better outcomes (Department of Defense, 2020). In a meta-analysis completed by Rodgers et al. (2020), autism symptoms showed no statistically significant improvements with higher intensity EIBI treatments as opposed to lower intensity EIBI treatments. It was also found that no one age group demonstrated improvement when correlated with the number of hours of rendered ABA services (Department of Defense, 2020).

Methods

In 2 years prior to the study, James acquired only two one-step directions, Joseph did not acquire any one-step directions, and Sean acquired three one-step directions. In addition, teaching participants to follow one-step directions may be conceived as a behavioral cusp (Rosales-Ruiz & Baer 1997), functioning as a prerequisite skill for more advanced behaviors. Multiple quantitative methods for single-case experimental design data have been applied to multiple-baseline, withdrawal, and reversal designs. In addition, several recently developed graphical representations are presented, alongside the commonly used time series line graph. The quantitative and graphical data analytic techniques are illustrated with two previously published data sets. Apart from discussing the potential advantages provided by each of these data analytic techniques, barriers to applying them are reduced by disseminating open access software to quantify or graph data from ATDs.

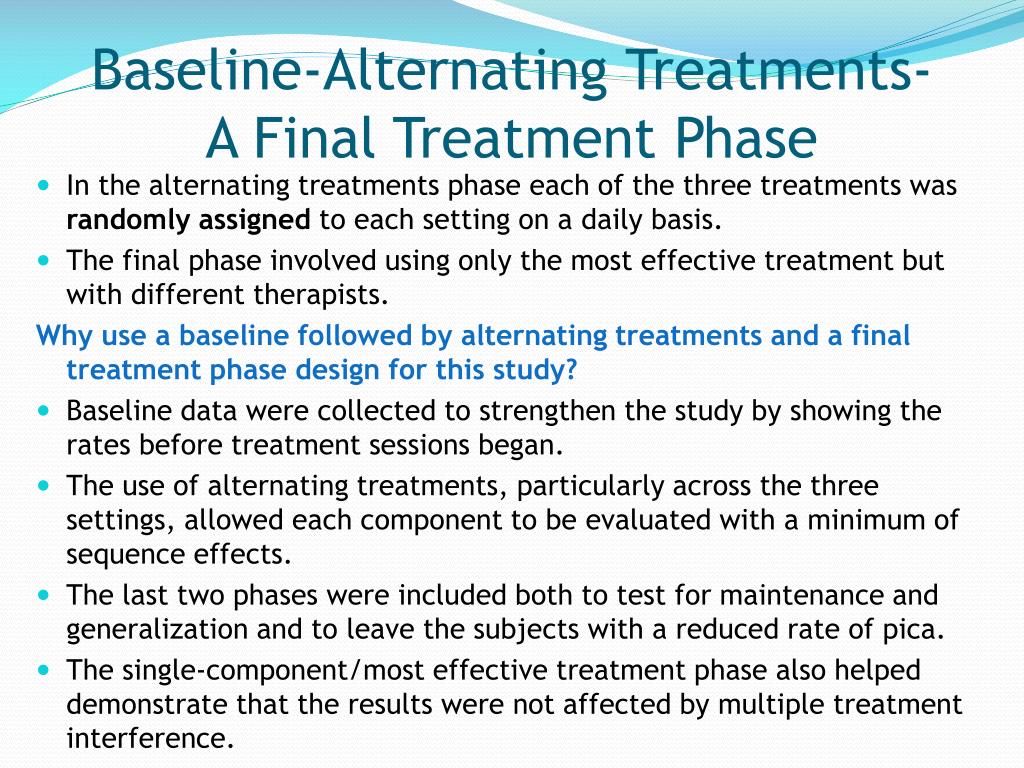

The major distinction is that the ATD involves the rapid alternation of two or more interventions or conditions (Barlow & Hayes, 1979). Data collection typically begins with a baseline (A) phase, similar to that of a multiple-treatment study, but during the next phase, each session is randomly assigned to one of two or more intervention conditions. Because there are no longer distinct phases of each intervention, the interpretation of the results of ATD studies differs from that of the studies reviewed so far. Rather than comparing between phases, all the data points within a condition (e.g., all sessions of Intervention 1) are connected (even if they do not occur adjacently). Demonstration of experimental control is achieved by having differentiation between conditions, meaning that the data paths of the conditions do not overlap.

Nonparametric statistical tests for single-case systematic and randomized ABAB…AB and alternating treatment ... - ScienceDirect.com

Nonparametric statistical tests for single-case systematic and randomized ABAB…AB and alternating treatment ....

Posted: Wed, 27 Dec 2017 00:58:04 GMT [source]

Topical Collection on Autism Spectrum

In contrast, a major assumption of the changing-criterion is that the dependent variable can be increased or decreased incrementally with stepwise changes to the dependent variable. Typically, this is achieved by arranging a consequence (e.g., reinforcement) contingent on the participant meeting the predefined criterion. The changing-criterion design can be considered a special variation of multiple-baseline designs in that each phase serves as a baseline for the subsequent one (Hartmann & Hall, 1976).

Alternating treatments design: one strategy for comparing the effects of two treatments in a single subject.

In this phase, the interventionist identified target responses to be used in the subsequent phases of the study. Ten new one-step directions were selected from Teaching language to children with autism or other developmental disorders (Sundberg & Partington 1998). The interventionists chose targets that were not part of the participant’s current or past preschool intervention. Additionally, no one-step directions that specifically stated an object manipulation (e.g., “Touch ball!”) or explicit body part manipulation (e.g., “Touch nose!”) were tested. During a trial, the interventionist provided one of the 10 one-step directions and waited 5 s for the participant to respond.

This evidence suggests there may be insufficient recent research justifying the need for high-intensity interventions, indicating that more research studies need to be conducted in the field of ABA in terms of assessing ABA impact with different or lower intensity interventions. The current findings are also consistent with other publications with respect to the comparison of ABA techniques, as 225 of the study records investigated the efficacy of various ABA methods compared to one another. Another review found that approximately half of the comparison articles investigated found that one method was better than the other(s), and the other half of the sample indicated that the methods were equally effective (Shabani & Lam, 2013). Thus, this result indicated that only half of the comparisons analyzed truly contributed to the best practices of ABA (Shabani & Lam, 2013).

On the surface, multiple-baseline designs appear to be a series of AB designs stacked on top of one another. However, by introducing the intervention phases in a staggered fashion, the effects can be replicated in a way that demonstrates experimental control. In a multiple-baseline study, the researcher selects multiple (typically three to four) conditions in which the intervention can be implemented.

Specific operational definitions for each response targeted in the study are provided in Table Table1.1. A correct independent response was defined as performing the specified response within 2 s of the presentation of the verbal discriminative stimulus (e.g., clapping when the interventionist said “Clap!”), in the absence of prompts. An incorrect response was defined as the failure to perform a response within 2 s of the presentation of the discriminative stimulus or performing an action that was different from the one specified by the interventionist (e.g., shaking the head when the interventionist said “Clap!”). A prompted response was defined as engaging in the correct response following the prompt. Finally, related to several different comments in the preceding sections regarding practical significance, there is the issue of interpreting effects directly in relation to practice in terms of eventual empirically based decision making for a given client or participant. At issue here is not determining whether there was an effect and its standardized size but whether there is change in behavior or performance over time—and the rate of that change.

Within the cognitive, language, and social/communication outcomes, 37%–40% of comparison records found that one method exhibited greater improvement than the other, whereas 47%–56% had mixed outcomes. This is similar for adaptive behavior, where 52% found that one method exhibited greater improvement and 39% were mixed. On the other hand, outcome measures for problem behavior and autism symptoms more clearly showed that one method exhibited greater improvement, at 65% and 70% (7 out of 10 records), respectively.

Like the AB design, the ABA design begins with a baseline phase (A), followed by an intervention phase (B). However, the ABA design provides an additional opportunity to demonstrate the effects of the manipulation of the independent variable by withdrawing the intervention during a second “A” phase. A further extension of this design is the ABAB design, in which the intervention is re-implemented in a second “B” phase. ABAB designs have the benefit of an additional demonstration of experimental control with the reimplementation of the intervention. Additionally, many clinicians/educators prefer the ABAB design because the investigation ends with a treatment phase rather than the absence of an intervention. Experimental control is demonstrated when the effects of the intervention are repeatedly and reliably demonstrated within a single participant or across a small number of participants.

As the understood spectrum of ASD and the diagnostic tools for ASD have changed drastically over the decades in which the investigated articles were published, the represented population may have also changed throughout the years, potentially influencing the acceptability of study findings (Reichow et al., 2018). Furthermore, the initial objective for this scoping review included searching across all NDD/D, not just ASD. Thus, the ASD MeSH term of “autistic disorder and autism spectrum disorder” may have potentially resulted in missed studies that included only AS or PDD-NOS diagnoses.

All three of these types of changes may be used as evidence for the effects of an independent variable in an appropriate experimental design. Number of phrases signed correctly during directed rehearsal, directed rehearsal with positive reinforcement, and control sessions using an adapted alternating treatments design. From “Acquisition and generalization of manual signs by hearing-impaired adults with mental retardation,” by Conaghan, Singh, Moe, Landrum, and Ellis, 1992, Journal of Behavioral Education, 2, p. 192. In ATDs, it is important that all potential “nuisance” variables be controlled or counterbalanced. For example, having different experimenters conduct sessions in different conditions, or running different session conditions at different times of day, may influence the results beyond the effect of the independent variables specified.

Comments

Post a Comment